EXPLORING THE NEW WAVE OF ECO TRAVEL ON THE AZORES

- Uncategorized

-

Feb 22

- Share post

A handful of prehistoric rocks that spike through the north Atlantic waves, where life bubbles on beneath active volcanoes. Here Azores expert Trish Lorenz takes a look at the new wave of eco travel on the islands.

In order to see this embed, you must give consent to Social Media cookies. Open my cookie preferences.

I’ve been visiting the Azores for the past six years, drawn to return again and again by the epic landscapes and sapphire sea, and because this is a wondrous, green part of the planet not yet conquered by humanity. It’s the first archipelago in the world to be assessed for EarthCheck certification, in recognition of its sustainable approach to tourism. But like most visitors, I have ventured infrequently beyond São Miguel, the largest island, with its colonial capital Ponta Delgada, hydrangea-filled hills and crater lakes. Further out in the Atlantic there are wilder isles, each one so different they could be the furthest planets of a solar system; from the lava-covered moonscape of Pico to the Avatar-esque Flores, where waterfalls plunge hundreds of feet over emerald-green cliffs.

This article was first published in the March 2020 issue of Traveller magazine

All nine islands were the result of volcanic eruptions, emerging from the depths of the mid-Atlantic Ocean, tiny atolls of black lava dominated by the mountains that spawned them. No one lived here until Portuguese explorers discovered the isles in the early 15th century and populated them with minor gentry, indentured servants, slaves and prisoners who had been given the choice between jail and exile. Living on Europe’s westernmost point, the people of the islands are hardier than their Portuguese mainland cousins: these descendants of whalers, fishermen, winemakers and farmers who carved their livelihoods out of stone have a sense of inner peace born from facing down the elements.

Pictured: White Exclusive Suites and Villas, São Miguel

Pico is a 50-minute flight from Ponta Delgada. From the air, it looks like a child’s drawing, an islet in the middle of cerulean water, the wobbly volcano that I set out to climb at its centre. I meet my guide, Daniel Pena, just before sunrise, the mountain tinged red in the pale light of dawn. He is calm, quietly encouraging and hikes the sheer slopes as easily as if negotiating a pavement, while I clamber, ungainly, beside him. It’s not his only talent. ‘I play the saxophone. I’ve just founded the island’s first jazz band,’ he tells me. ‘After Cuba, Cape Verde and Ireland I think we are the world’s fourth most musical place. The good thing about living in a region where not much happens is you have all this time to do whatever you want.’

Pictured: Cascata do Poço do Bacalhau waterfall, Flores

When we reach the first plateau, the mountain is casting a pyramid-shaped shadow across the land below. Clouds float beneath us, the island spread out in shades of green criss-crossed with black stone walls and the dark craters of more than 200 volcanoes. After a steep, four-hour climb through an extra-terrestrial environment of wrinkled, cooled lava and clumps of purple heather and ferns, I’m 7,546ft up Mount Pico. The peak is visible one rocky chasm ahead. As I approach it, the stones beneath my hands become hot to the touch and steam whistles from a crack beside my head. The feeling I’ve had all morning, that I’m scaling some vast prehistoric beast, emerges again: after the huge grey boulders of its vertebrae and the smooth muscles of rippled magma, I’m finally reaching its snorting, breathing crown. The view from the summit is spectacular, a satellite’s map of the other isles that make up this corner of the Azores: from Faial, where cross-Atlantic yacht crews gather for a final touch of land, to slender São Jorge, fringed by surf.

Pictured: Fajã de Santo Cristo beach, São Jorge

Along with its volcanoes, Pico is known for wine – its 550-year-old vineyards are a UNESCO World Heritage site. Fortunato Garcia, an art teacher by day and winemaker at other times, invites me to his adega, a rustic stone storehouse at the edge of the family estate. The back wall is covered with barrels of ageing wine but the centrepiece is a 13ft-long wooden table flanked by mismatched chairs. These houses – as well as the little churches with bright interiors found in every village – are the social glue that hold Pico’s small community together. ‘Everyone here owns a vineyard,’ says Garcia. ‘It’s tradition that visitors come to help with the harvest and then come to the adega and help with the drinking. Not that long ago, people used to give kids a few drops of wine in their milk.’

Pictured: Vegetation meets volcanic earth on São Jorge

The people of Pico are hardy drinkers. Garcia’s Czar-label wine is made using the island’s grapes, picked very late, and has the distinction of being among the strongest anywhere in the world: one vintage reached an intoxicating 20.1 per cent. It is smooth and dry, and after two glasses, a river of warmth runs through me, the ache in my legs from climbing disappears and a smile creases my face.

Pictured: Vila Franca do Campo island off São Miguel

The next morning, surprisingly headache-free, I board a ferry for the hour-long sail to neighbouring São Jorge. Luís Bettencourt meets me off the boat. He was a child when an earthquake shook the island’s foundations in 1980. ‘I remember clinging to my mother’s legs as the ground moved,’ says Bettencourt, now in his 40s. Afterwards, many emigrated – more than half of all Azoreans now live abroad, mostly in the USA and Canada – but Bettencourt’s family stayed and he soon discovered that he thrived on adrenalin. He built his first abseiling kit at 12 and later founded an adventure-sports company to the general incomprehension of his relatives, for whom living on an active volcano in the middle of the Atlantic was presumably adventure enough. He wants to lead me to a hidden surf spot only accessible by hiking ancient paths down forested cliffs.

Pictured: Santa Bárbara beach on São Miguel

There’s a local word, bruma, meaning the mist and fog that comes from being inside low cloud. As we start our hike, it descends. We trek through the damp haze of the forest accompanied by calls of unseen birds and the faraway burble of waterfalls. It’s humid. Moss covers the worn stone steps of the steep, winding path. Our feet crush wild mint, releasing a fresh scent, and yam leaves bigger than plates brush our legs. Distant mountains slide in and out of view. I feel as if spotting a dinosaur munching from a tree branch on their misty slopes is not entirely out of the question.

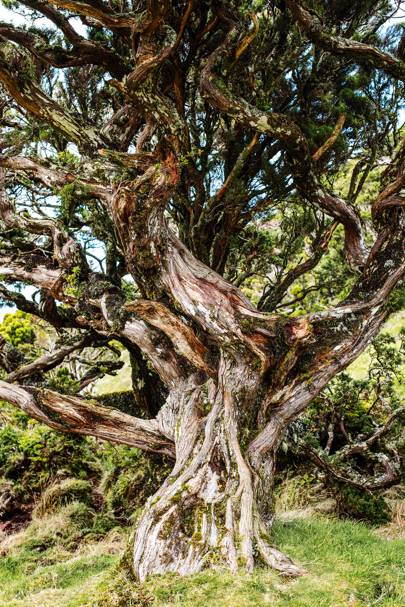

Pictured: Jurassic plants on Flores

After an hour of walking downhill, we emerge from the bruma onto a low plateau above a village of stone houses and a whitewashed church on a narrow peninsula between the mountains and sea. This is Fajã de Santo Cristo lagoon. Largely abandoned after the earthquake, it has recently been rediscovered by surfers. There are virtually no people here, no electricity, no internet, no roads, no cars – and no easy way in or out.

Pictured: Santa Bárbara Eco-Beach hotel on São Miguel

The waves are less than three foot in height today, but the rocky seabed means that even at this size they are powerful enough to ride. Three surfers pad past us to the ocean, their boards forming long fins behind them. Rodrigo Herédia has the tousled hair of a man who has spent much of his life immersed in salt water. The Portuguese former surfing champion has travelled the world, but Fajã de Santo Cristo is his favourite spot. ‘This island is a mystery in the middle of the Atlantic,’ he says. ‘It’s like Indonesia was 30 years ago. There’s a long point break, perfect waves and the water is 24˚C, so you can surf in shorts. Often, you’re the only one here.’

Pictured: Vegetation on Flores

Sitting in the lee of the mountains, listening to the waves rolling onto the stony beach, I survey the abandoned houses around me that are losing the fight against plants reclaiming the land. I’m struck by the fleeting nature of human endeavour. The idea brings me surprising tranquillity, the certainty that all things will pass.

Pictured: Twisted tree trunk on Pico

After São Jorge I head to Flores, perhaps the most beautiful of the nine islands, definitely the wildest and most elemental. The westernmost point of the archipelago, it lies some 320 miles and a two-hour flight from Ponta Delgada. Green meets blue wherever I look: sea and sky border bright mountains; tall waterfalls drop into streams; alpine forests nudge crater lakes. Here, standing on the cliffs, the inky ocean curves 270 degrees around me, as if I’m on the prow of a boat. Towering cumulus sits like a top hat above the island of Corvo on the horizon. Waves attack the jagged columns of black basalt that thrust from the water below, crashing in silvery eddies at their bases. The wind is constant: even on a sunny day, the air has an impatient quality. The impression of smallness I had at Fajã de Santo Cristo returns, but it’s paired with a feeling of vulnerability. On this island, I have a sense of what life must have been like before humans so fully dominated the planet.

Pictured: Dolphins on São Miguel

Just 4,000 people live on Flores and young Francisco Pimentel knows them all. As we drive, his index finger lazily salutes every car we pass. Fajãzinha, his hometown, which has only 61 residents, is embedded on a steep hillside facing the sea. The wooden floorboards in the local church were salvaged centuries ago from ships wrecked on the cliffs below and inside its small cottages are tiled images of religious icons: Our Lady of Hope, Our Lady of Miracles.

Pictured: Plants in a bathroom at White hotel

Pimentel shows me his great-grandmother’s house, white with a red door and small windows that look to the water. For Azoreans, the ocean is much more than just a view. ‘Maresia,’ says Francisco, using a Portuguese word that translates as salt spray but which is used to mean the scent of the sea. ‘An Azorean needs maresia. We have to see the sea, we have to hear the waves. I need to know it is always there. Even if I’m not looking at it, I want to know it’s over my shoulder somewhere. If I can’t see the sea every day, I feel like I’m in jail.’ That night, I sleep with the windows open, listening to the restless ocean and the wind throughout the night.

Pictured: São Jorge hills

CORVO

CORVOOn the day I’m due to travel to Corvo, the inter-island ferry is cancelled. Instead, I’m taken in a nippy inflatable boat the 15 miles or so across the ocean. On the journey, the dark shadow of a marlin longer than the vessel flicks past and a pod of 15 dolphins carves arcs in the indigo water beside us. Corvo is tiny, just a volcano and robust cows grazing the windswept pastures on its flanks. There is only one village, with twisting, narrow streets – designed to help defend against pirates – a bird-watching centre and a small museum dedicated to the island’s history. But it’s locked; Senhor Filipe, who holds the key, is busy butchering a pig. Calls are made and eventually he appears, eyes bright, thinning hair brushed over a nut-brown pate and with two front teeth that are shorter than others, lending his smile a triangular tilt.

He points out a spinning wheel that belonged to his grandmother and gives me two balls of oily wool, one dyed the traditional royal blue of the islands’ cloth, as a keepsake. I’m drawn to a black-and-white picture on one wall of a toddler in the back of a bullock-drawn cart. I hazard a guess that it was taken in the 1900s. Senhor Filipe shakes his head. ‘No,’ he says. ‘It was the early 1970s. I know because that’s me in the cart.’ On the Azores, time is slow.

Pictured: Lagoa Negra and Lagoa Comprida, two lakes on Flores

SÃO MIGUEL

SÃO MIGUELI have mixed feelings about my return to the buzz and activity of São Miguel, but lunch with a friend at Otaka in Ponta Delgada reminds me of the pleasures of urban life. Chef José Pereira combines Azorean ingredients with Japanese techniques: wild, line-caught blue-fin-tuna sashimi; creamy limpets served with yuzu soy. But later that afternoon, craving the hazy solitude I felt on the outer islands, I head to Furnas, a small town a 45-minute drive north-east, which sits in the crater of an active volcano that spits, steams and emits a scent of sulphur. Locals cook food in it and bathe in its medicinal thermal pools. Before dusk, I walk barefoot and alone down to one shrouded by Jurassic trees, mist clouding above it. I float on my back, watching the sky change through the colours of hydrangeas, from pale blue to red. Surrounded by mountains and enveloped in warm, soothing water, I am as weightless and still as a baby in the womb. There is no sound.

Pictured: A rock-fringed lagoon on Flores

Source: cntraveller.com